|

After the Etnika project aiming at presenting old traditional Maltese instruments and experimenting their sounds while introducing a fusion with contemporary ones, the Maltese musicianAndrew Alamango embarks on the boat of a new adventure carrying the same quest for past music. After the Etnika project aiming at presenting old traditional Maltese instruments and experimenting their sounds while introducing a fusion with contemporary ones, the Maltese musicianAndrew Alamango embarks on the boat of a new adventure carrying the same quest for past music.

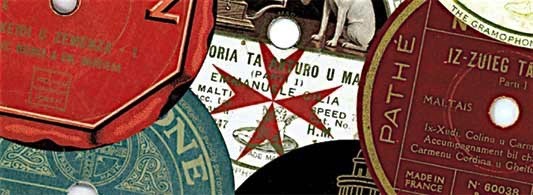

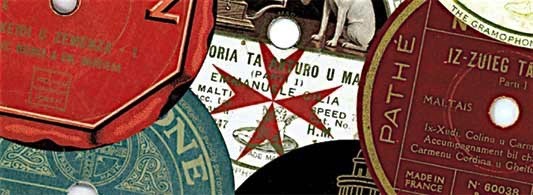

His passion for Maltese and Mediterranean musical heritage brings him to discover a collection of old gramophone records dating back to the 1930’s.The records present a series of Maltese folk singers and musicians that were sent to Tunisia and Milan to record their music with major European labels such as HMV, Polyphon, Odeon and Pathé. This was happening in the framework of a larger worldwide phenomenon consisting of recording folk music. It is a coincidence that during this same period social sciences, especially anthropology, were developing? Wasn’t it a time when anthropologist were still sent to developing countries to study their cultures and gather as much information as possible?

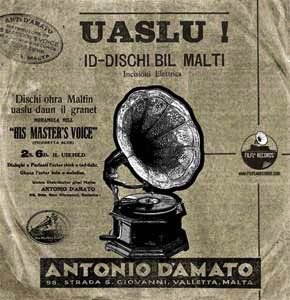

Andrew Alamango decided to build a project with the objective of safeguarding and preserving this collection of gramophone records naming it Malta’s Lost Voices , Ilhna Mitluf a in Maltese. This initiative was supported by the Maltese National Archives and the Ministry of Education in the framework of the National Memory Project.

Malta’s Lost Voices is about working on historical memory through music in a country that needs to rediscover its musical heritage. The young Maltese seem to need to reconnect with the past, know where they come from in order to be fully in the present and then move on to the future. If the tree has no roots it can give no new leaves let alone fruit. Beyond local and national interests, through this project, Andrew Alamango is in search for links and common roots and also divergences between Maltese music and music from other Mediterranean countries.

This initiative comes at a time when the potential of the creative, artistic and cultural spheres (all sectors taken together) in Malta is growing exponentially. Innovative theatre productions are popping. Contemporary art exhibitions are starting to flower. And when it comes to literature, as Maria Grech Ganado believes, there has “never been so much literary ferment in the Maltese islands since the sixties.” Young writers are emerging experimenting with the Maltese language.

The Malta’s Lost Voices project is implemented in two phases. The first phase of consisted in research, collection of information and documentation of these records. For preservation purposes, the sounds of some 78rpm gramophone records have been restored and digitalised and the information gathered has been input in a database. The idea is to make this music durable and accessible to people.

The second phase consists of the publication entitled Malta’s Lost Voices, The Easly Shellac Recordings (1931-32) Volume 1 . This 50-page book with a CD features tracks from the original records and photographs and newspaper cuttings of the same period. The publication will be launched in Malta on the 26th of November 2010.

® Andrew Alamango Andrew Alamango accepted to answer our questions.

What is this 1930’s folk music recording phenomenon all about?

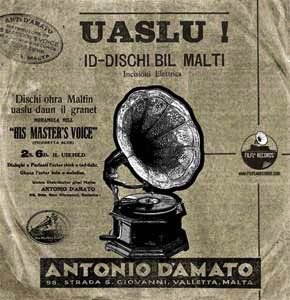

The recording of Maltese folk and popular music in the early years of the 1930 was part of the worldwide phenomenon when the recording conglomerates, as early as 1900 decided to record the music of every country realising that there was a market for it far beyond the palate of the western world.

This meant that engineers would be sent out with the task of documenting the music of each country and sign on artists before their competitors would. It was a commercial impetus which led to the recording of stars like Caruso and Oum Khalthoum and other local artists worldwide. Due to this development, music became an attractive new product. This gave rise to the ‘ethnic series’ of recordings which documented much of the folk and popular traditions of the world.

By 1931, around the time that the major companies of the world merged to form EMI and avoid further fragmentation of the world markets, recording centres like Milan, Paris, London and Barcelona were established and became key points for recording music. The Maltese, Sicilians and Sardinians were in fact sent to record in Milan’s HMV studios.

Over two brief years, numerous artistes, composers, and singers were recorded, reflecting the vibrant musical activity of the day. It reflects a strong musical and national identity and a clear awareness of the imported styles of tangos, fox trots and waltzes. Clearly local musicians and composers were influenced by the earlier records of music in local music stores, of American, English songs and Italian operetta. The music recorded in these two years, in Milan, Tunis and Valletta was a social phenomenon as it acted as a self-reflective tool when the Maltese music was played back for the first time to its people. It was also a strong statement in view of the socio-political clash of language, ousting Italian in favour of Maltese and English.

Where and how did you find these gramophone records?

They started appearing as I worked in folk music research, I read an extract in G. Cassar Pullicino’s book on Maltese oral folk poetry and then started to realise that some were still around in private collectors hands, families who had inherited the records, collectors and international discographers, and the odd curious shops and flea markets. They eventually showed up and I realised they were not one offs… I started to devise the catalogue listings with help form some of the well known discographers world wide…and it turned out to be an investigation of music and Valletta society in the 1930s. Not all were in good shape, but some were brand new and never been played before… others were worn an needed care and handling.

How do you explain the loss, the big gap of Maltese music, then and now? And tomorrow?

I realised that there was a big lack of reference and accessibility to our audio heritage. This is the earliest documented sound of the country and the first step in creating the sound archives of the country. A database has been developed out of this material and will be at National archives for public access and research. Now there is a reference and it is the basis of similar projects I intend to embark on with filfa records. I’m doing this because it has not been done before and it so important to work on memory.

If you talk about a Mediterranean identity, it cannot exist without a reference to our recent past, especially music. The idea is to release digitalised music compilations. with this first publication referring to folk singers, guitarists, the biography of poets and composers. All these forgotten lost voices will now be accessible. The technology today allows all this today. Another important aspect I intend to focus on in the coming years is the re-interpretation of this music for the sake of preservation and collective memory. The idea is to use this repertoire as a basis for creativity.

® Andrew Alamango How do you intend raising people’s awareness with regards to this rich musical heritage?

The songs will be available in bookshops but also online. It needs to be within reach and accessible, attractive, listenable. From the feedback I am getting it is already a successful venture as it is nostalgic for older generations and new to young generations, who want to rediscover their music. Education is the key. I hope educational institutions will take this on for it to be studied and analysed. This is part of our heritage, our memory, not only as Maltese but also as part of the Mediterranean.

How do you place this local project in a larger Mediterranean framework?

It is clearly part of Mediterranean heritage, as a story of the activity which ties in all the countries involved in the making of this story and even wider than that…This project has a massive appeal to Maltese migrants. Not only Mediterranean but all around the world. The records were exported to the migrants in North Africa (Alexandria, Algiers, Tunis) in the thirties evoking nostalgia for the motherland. Today the relevance of this material is again self reflective in a Mediterranean context. The language, its use, the dialect, the identity with the language, the music styles and their reinterpretation in Maltese, their common elements with other Mediterranean styles of music … I could go on forever.

–

More information:

http://maltashellac78rpm.wordpress.com/

www.filflarecords.com

http://eng.babelmed.net/arte-e-spettacolo/129-malta/6179-rediscovering-malta-s-past-voices.html |